Contributed by ATS’s 2004 Society for Neuroscience Poster of the Year Award Winner:

Michelle Pearson, Purdue Pharma, Discovery Research, 6 Cedar Brook Drive, Cranbury NJ 08540

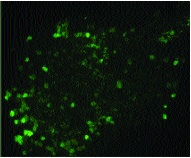

Neuropathic pain results in hyperalgesia and allodynia. It has been proposed that sprouting of myelinated touch-responsive Aβ-fibers into the innervation territory of pain-sensitive C-fibers in the spinal cord contributes to these abnormal behaviors.[1] The extent of sprouting has recently been challenged and it has been proposed that C-fibers rather than Aβ-fibers are involved. We have investigated whether selectively ablating a population of small-diameter nociceptors (see Fig. 1) and their associated C-fibers, reduces axotomy-induced sprouting. We ablated this population of sensory neurons by intraneural injection of isolectin B4 conjugated to saporin (IB4-SAP, Cat. #IT-10).

Methods: Male, Sprague-Dawley rats received an intraneural injection (directly into the sciatic nerve at mid-thigh level) of either IB4-SAP (2 μl of 0.66 μg/μl) or PBS (2 μl of 0.01 M). Two weeks later, the left sciatic nerve was again exposed and tightly ligated. In the control animals, the nerve was exposed but not ligated. Two weeks following nerve ligation, cholera toxin-β (CTB) subunit conjugated to FITC (2 μl of 20 μg/μl) was administered into the left sciatic nerve in both experimental and control groups. Three days post CTB-FITC injection, animals were perfused with 4% formalin and the relevant tissue was dissected and post-fixed overnight in the same fixative. The spinal cords and dorsal root ganglia were sectioned using a microtome at 60 and 40 μm thickness, respectively. Sections were stained using either IB4-FITC or goat anti-CTB-FITC.

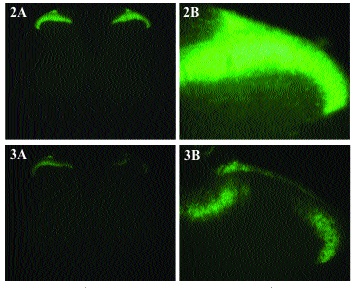

Results: IB4-SAP treatment resulted in a reduction of IB4 staining in lamina II of the spinal cord as compared to PBS-treated animals (Fig. 2 compared to Fig. 3). This result confirms previous work demonstrating that, when injected into the sciatic nerve, IB4-SAP is retrogradely transported to the dorsal root ganglia where it is subsequently toxic to a subpopulation of small diameter nociceptors.[2] Image analysis demonstrated that the decrease in IB4 staining was both large and statistically significant as compared to PBS-injected controls (p ≤0.05; Fig. 4, not shown).

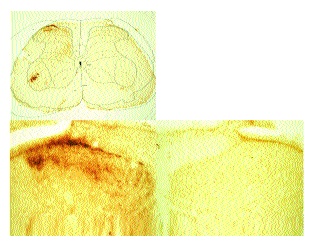

As previously described[1] sections from rats that received a sciatic axotomy followed by intraneural CTB displayed an obvious presence of CTB in lamina II in addition to the motor neurons, laminae I and II-IV (Fig. 5). In these sections the borders of lamina II were not discernable. In all cases, lamina II was devoid of stain on the side contralateral to the injection.

Spinal cord sections from rats that had received sham surgery followed by intraneural injection of CTB displayed prominent CTB immunostaining in the motor neurons, lamina I and lamina III-VI on the side ipsilateral to the injection (Fig. 6). Lamina II was devoid of positive immunostaining for CTB and boundaries between lamina I, II and III (arrows) were easily discernable.

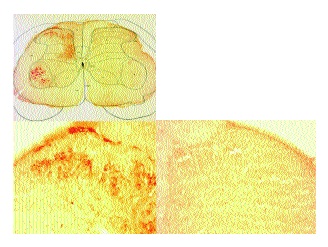

Spinal cord sections from rats that received an intraneural IB4-SAP injection and sciatic axotomy followed by an intraneural injection of CTB (Fig. 7) displayed prominent CTB immunostaining in motor neurons, lamina I and lamina III-VI on the side ipsilateral to the injections. Lamina II was devoid of positive immunostaining for CTB.

These data confirm the previous report that intraneural IB4-SAP ablates a population of small diameter nociceptors in the dorsal root ganglion and reduces the quantity of IB4-positive terminals in the spinal cord. Following ablation of this cell population, the extent of axotomy-induced CTB staining in lamina II is reduced as compared to control animals. This study strongly suggests that C-fibers contribute significantly to CTB staining that is observed in the spinal cord following nerve injury.

Figure 3. Intraneural IB4-SAP reduces Isolectin B4 staining in lamina II.

Figure 4. Not shown.

References: (back to top)

- Woolf, CJ et al. (1992) Nature, 335:75-78.

- Honda, CN et al. (2001) Neuroscience, 108:143-155.